09.05.2020

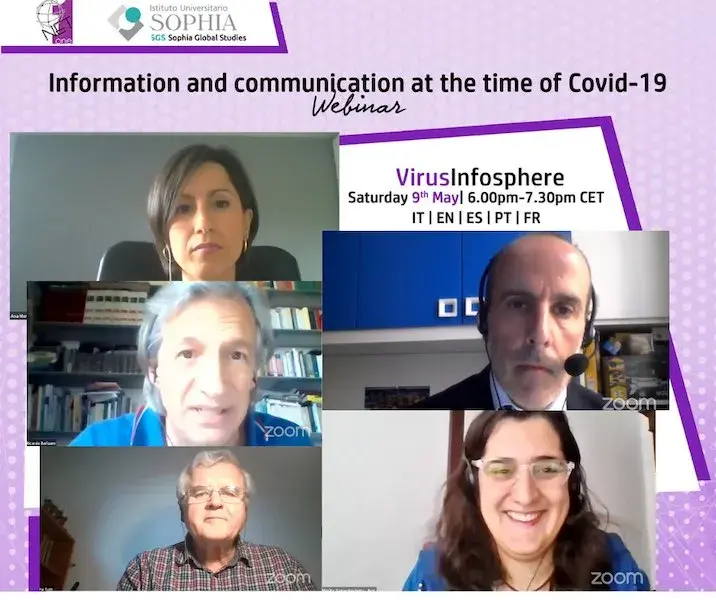

- VirusInfosphere is the title of the first of three international webinars on “Information and Communication in the Time of Covid-19” promoted and organised by NetOne in collaboration with the Sophia Global Studies Research Centre in May – June 2020.

How has journalism – public and private – responded to this crisis? Has it moderated the scandalous and spectacular tones? Has working remotely, with less grip on location, damaged the quality of reporting? Is there greater attention to truth, greater trust in the age of fake news? In the face of complex issues, is there a more dialogic approach to the practice of the profession?

The webinar on 9 May sought light from asking these questions together: journalists and lecturers, from different geographical and cultural viewpoints.

In times of crisis, there is a greater need for quality information, according to moderator

Michele Zanzucchi, convinced that “after the lockdown we will know how to better manage our information and communication world, having rediscovered the sense and importance of real, physical communication, and the awareness of the great possibilities and limits of digital communication”.

For Riccardo Barlaam, US correspondent for Il Sole 24 Ore, President Donald Trump’s mode and style of communication, accustomed to Twitter much more than to classic morning press conferences, had already radically changed the job. Unsubstantiated claims about the health crisis imply the challenge to inform with thoroughness, delving into all aspects of a news story.

From Chile, journalist and university lecturer Alberto Barlocci notes “an increased search for the good and the truth and an irresponsible dissemination of fake news, even deliberate”. On the other hand, the current construction of choices on the basis of inadequate data and information is also a consequence of the spread of large “fake news” established for decades on the basis of poorly grounded lines of thought, which have “dismantled the capacity to produce ideas on the basis of rigorous thinking”. One example is the theory of a market “absolutely capable of solving all crises without the need for external intervention”: “the market will not be able to solve this crisis without the multimodal intervention of public authorities”. “The challenge for us in the media is to construct epistemologically serious thinking”.

A “dialogical journalism” is what Hungarian Professor Pal Toth, lecturer at Sophia University Institute, advocates for. It is a way of generating information that is particularly necessary in critical scenarios and highly polarised or complex contexts, which requires listening to and understanding all parties involved in the facts and dialogue between information professionals as a method of searching for the truth. “Homo sapiens is not an individual agent. Anthropologically, human action requires a triangulation: facing the world and dialoguing with each other, collaborating”. The crisis of today’s culture comes from acting alone. “We must learn to work together again” when addressing issues such as migration, global warming or Covid, “triangulating” with reality and with each other. Toth briefly reports on three stimulating initiatives promoted by NetOne, on war and migration narratives and on understanding cultural differences between Western and Eastern Europe. Regarding social media, where “interpretation bubbles” are frequent, the challenge is to help manage diversity and acceptance of others. There are encouraging examples, such as the “Germany Speaks” column in Die Zeit newspaper, which focus on understanding otherness.

Spain’s Ana Moreno describes the practice of television journalism in her country at this unprecedented time. A common element is the general unpreparedness to work from home, with fewer opportunities for control. In television news, “a sense of responsibility has prevailed” and, particularly in the regional media, a commitment to public service with “a positive and social approach”. “More space than ever before was devoted to good news”. In the big media groups, sensationalism and spectacle were moderate and, in general, the media groups were dedicated. The government responded to the health crisis with information control “close to censorship”, which provoked popular protests online.

From the Democratic Republic of Congo, Emmanuel Badibanga echoes her, attesting that even there the conscience and will to be a public service, and to educate as well as inform, prevails, despite the precarious working conditions of the lockdown and the difficult socio-political and economic context.

Radio too has had to adapt to the changes. Vatican Radio has “revolutionised the schedule’, with a double daily broadcast: ‘In prima linea – vivere con la fede al tempo del Coronavirus’. Fabio Colagrande notes an increase in listeners’ interest in the station, who see in Pope Francis “a point of reference that is not only religious”, in times of emergency and uncertainty. “Through social media, we have been able to intercept the need for information, capable of creating community, generating trust and giving hope” as an alternative to the coldly statistical, alarmist or sensationalist information. “Some people told us: ‘I listen to you because there is a constructive reading from you, open to the future'”. The impossibility of fieldwork boosted web research and left time for study and reflection, but a quality service was only possible thanks to the “human capital of direct knowledge accumulated over decades of work”. “Not reporting from lived experienced, only from the desk, is irreplaceable”. Journalism that shows alternative positions to the forced bipolarity of Facebook is necessary. Even if social media can be “stimulating” because they force “a deepening, a clarity and a capacity for synthesis that we might not have spontaneously”.

Romé Vital speaks of the Asian context, where culturally one takes a submissive attitude towards authorities, and only then questions them. This is reflected in government communication, which “tends to manage and sometimes control information” for reasons of public order. In the case of the Philippines, in times of Covid there is an “intense thirst for information among the people, who have resorted to other sources to fill the information vacuum” left by the institutions. Even heroic communicators were seen in the independent media. The largest television network was blacked out by the government, to the outcry of many Filipinos, but continued to broadcast online, producing content that was rebroadcast by other local networks.

From Argentina, Marita Sagardoyburu of the national public radio station emphasised the importance of a “dialogue with oneself” in order to maintain freedom of conscience by learning to identify the margins within which to move, having to follow directives from superiors, which at times may not be entirely independent from political power.